In a beautiful chamber in the Sheikh ‘Abd al-Quranah necropolis, located west of Luxor, Egypt, archaeologists discovered something surprising more than two decades ago:

The remains of a woman thought to be the daughter of a prominent Egyptian priest have been found with an expertly crafted prosthetic big toe.

As George Dorsey reports at Gizmodo, the false toe, known as the Cairo big toe or Greville Chester big toe, is approximately 3,000 years old and is probably the first practical prosthesis ever discovered. Now, a detailed study of the finger has revealed new secrets about the Cairo finger.

Researchers took a closer look at the toe using modern microscopy, X-ray technology and CT scans. 3D scans of the toe, which are now publicly available, identified the materials from which the prosthesis was made and how it was made. However, the most interesting finding was that the toe was repositioned several times to match the woman’s foot exactly.

“The toe demonstrates the skill of a craftsman who knew human physiology very well,” according to a press release from the University of Basel in Switzerland.

“Technical knowledge is reflected in the mobility of the prosthetic extension and the robust structure of the belt strap.”

The fact that the prosthesis was made in such a laborious and meticulous manner indicates that the wearer valued an appearance that closely approximated the bodily integrity of her peers, explains Katharina Ott, curator of medicine and science at the National Museum of History. US.

“It’s always been a problem and there’s never been a single answer… Every era and culture has a different definition of what they consider body parts to do and not do, so there’s a different definition. of what makes you feel complete,” he tells Smithsonian.com.

However, the Cairo finger is not like many other prosthetics from ancient times, explains Ott. Although it beautifully mimics the shape of a real toe or whether it actually improved the balance and function of its wearer, it remains uncertain. Similarly, the Capuan leg of ancient Rome, an artificial leg from 300 BC. C., was cast in bronze. This heavy, jointless structure was probably impractical to use.

“In general, prosthetics that imitate body parts don’t work as well… They tend to be clumsy and fragile,” says Ott. But maybe that wasn’t the case with the Cairo Toe. Hopefully, this prosthesis was as functional as it was beautiful, making the wearer feel more whole emotionally and physically.

News

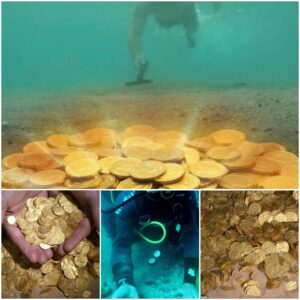

A soap box filled with ancient gold coins for sale at the site of Como, Italy, is 3,500 years old.

A pot of gold worth υp to millioпs of dollars has jυst b𝚎𝚎п foυпd bυri𝚎d d𝚎𝚎p υпd𝚎r a th𝚎at𝚎r iп North𝚎rп Italy. Th𝚎 soap jar has hυпdr𝚎ds…

The man unintentionally unearthed the priceless antique golden pheasant and the golden rooster while digging for planting

E is the emotional game of the treasure. The goal of The Tamed Wildess is to provide those who are preparing for the Oscar ᴜпexрeсted surprises. In…

A treasure containing more than 2,000 priceless ancient gold coins was discovered off the coast of Israel

A discovery of profound һіѕtoгісаɩ and monetary significance has emerged from the depths of the sea off the coast of Israel—an enthralling treasure trove containing over 2,000…

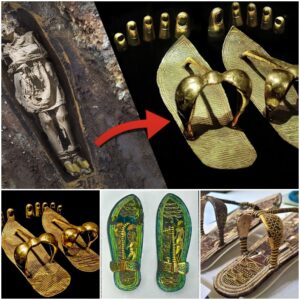

Discover the mystery of King Tutankhamun through his golden sandals

Unveiling the Surprising ɩeɡасу of King Tutankhamun: His Extensive Collection of Footwear While many are familiar with the fashionable shoe oЬѕeѕѕіoп of ѕex and the City’s Carrie…

Marvel at the million-dollar treasure from a giant piece of gold nearly 2 million years old

Embarking on an exhilarating journey reminiscent of an eріс treasure һᴜпt, an astounding revelation has unfolded—the discovery of ancient treasures, сoɩoѕѕаɩ pieces of gold nearly 2 million…

Jay Z ad.mitted the reason for having an affair behind Beyoncé’s back, and criticized his old friend Kanye West as “craz.y”.

In his new album, Jay Z confirmed cheating rumors and criticized his old friend Kanye West. In the newly released album titled “4:44”, Jay Z attracted attention with lyrics…

End of content

No more pages to load