Archeologists in the Mexico City district of Azcapotzalco have discovered the base of the pre-Hispanic house and other building remnants of an ancient settlement.

In a declaration, the INAH confirmed that the finds in the historic center of the northern borough were part of the ancient altépetl, or city-state, of Mexicapan.

The city came into being when inhabitants of the Aztec or Mexica, capital of Tenochtitlán conquered the dominion of Azcapotzalco in 1428 and divided it into two autonomous settlements – Mexicapan and Tepanecapan.

The “domestic platform,” as INAH describes the foundations of the home, and the other structural remains are believed to have been part of a residential neighborhood within Mexicapan that was occupied by the city’s elite.

Measuring eight meters by six meters, the stone foundations of the pre-Hispanic house are among the largest ever found in Azcapotzalco, said INAH archaeologist Nancy Domínguez Rosas. The archaeological rescue team she heads also unearthed the remains of stone walls on the perimeter of the platform that measures between 50 and 70 centimeters.

The discovery is located in the historic center of Azcapotzalco.

The foundation is well preserved, Domínguez said, although the wall remains show signs of damage from more recent construction.

Archaeologists believe that the platform was built in two separate stages, the first of which corresponds to the late post-classic period between 1350 and 1519 AD. When the second phase of construction took place has not yet been determined.

Archaeologists found the platform while working alongside a municipal government team that was installing a tension fabric structure on Paseo de las Hormigas (Promenade of the Ants), which is part of the Azcapotzalco Park.

Domínguez said that 31 holes between one and two meters deep were dug for the slab foundations of the shade structure.

The structural remains of the Mexicapan neighborhood were discovered at a depth of 1.2 to two meters in front of the Azcapotzalco market, she said.

In addition to the domestic platform, archaeologists discovered the remains of other residential structures including one that measures 1.72 by 1.75 meters. All of the structures were made out of high-quality materials, leading archaeologists to conclude that they housed the elite and upper classes of Mexicapan society.

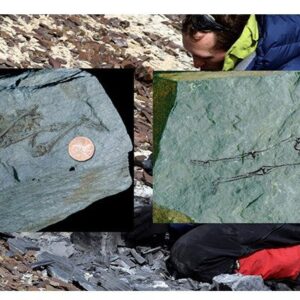

The archaeological rescue team has also discovered artifacts made out of both stone and bones.

Domínguez said the presence of the INAH team while the municipal employees are working in the area ensures that archaeological remains are not damaged, adding that archaeologists will continue to work to determine if there are any more pre-Hispanic structures in the area.

After they have been examined, the structures will be covered with geotextile, soil, and limestone to avoid their deterioration.

The discovery of such remains allows archaeologists “to recover information and contrast it with the information provided by historical sources,” Domínguez said, adding that the aim is to develop a greater understanding of “the way of life” of the residents of Mexicapan.

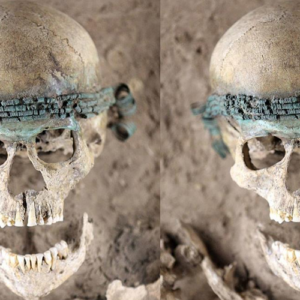

She also said that there is evidence that there were chinampas, or floating gardens, in the elite neighborhood and that human burials took place there.

The information . . . helps us to gradually reconstruct the puzzle of the urban configuration of Azcapotzalco in the pre-Hispanic era,” Domínguez said.