An ancient graveyard containing dozens of skeletons with deformed elongated skulls is showing how people lived during the trouble and turmoil sparked by the Fall of Rome.

Known as the cemetery of Mözs-Icsei-d?l?, the fifth-century CE burial ground can be found in present-day Hungary. The site was first excavated in the 1960s, followed by later digs throughout the 1990s, which revealed the skeletal remains of at least 96 people. Archaeologists from Curt-Engelhorn-Center for Archaeometry in Germany and Eötvös Loránd University in Hungary have recently used isotope analysis and biological anthropology techniques to get deeper insights into the dozens of lives laid to rest here.

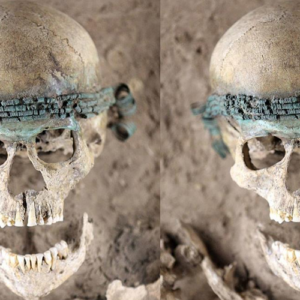

Reported in the journal PLOS ONE, at least 51 of the burials were found to have artificially elongated skulls that appear to have been shaped by bandage wrappings, making the cemetery home to the largest concentration of this cultural phenomenon in Central Europe. As well as the deformed skulls, the cemetery also contained three distinct groups buried separately across two or three generations. As this new research has highlighted, the three groups were a diverse bunch that neatly reflect the colossal cultural changes that were occurring at the time. Grave 43 contains the skeleton of a girl with an artificially deformed skull, placed in a grave alongside a necklace, earrings, a comb and glass beads. Wosinsky Mór Museum, Szekszárd, Hungary.

Grave 43 contains the skeleton of a girl with an artificially deformed skull, placed in a grave alongside a necklace, earrings, a comb and glass beads. Wosinsky Mór Museum, Szekszárd, Hungary.

The earliest of the distinct burial groups at Mözs-Icsei-d?l? contains a small number of local people buried in graves built in a brick-lined Roman style. The next group, buried a few decades after the earliest group, were “outsiders”: twelve individuals whose bones show they all shared a similar diet, but they did not originally come from the region. They also appear to have introduced new traditions to the area, such as burying goods in the graves and skull deformation. The third group of later burials featured people who appear to have blended the old Romanized culture with various foreign traditions, including the skull deformation.

In this particular instance, it remains unclear where the tradition of skull binding was brought from, although it appears to have originated somewhere outside of the Roman Empire’s influence. Archaeologists have found elongated skulls from regions across Central and Eastern Europe, including modern-day Austria, Croatia, Hungary, Romania, Serbia, Slovakia, and Slovenia. Further afield, the practice has also been documented in the Americas, Asia, and Africa. Its meaning is likely to have differed from culture to culture, although researchers generally believe it was used to express some kind of social status.